Youth's Lives Every Day

Content Warning: This story explores suicide loss and attempts. For support, our trained crisis counselors are available 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386 via chat www.TheTrevorProject.org/Get-Help, or by texting START to 678-678.

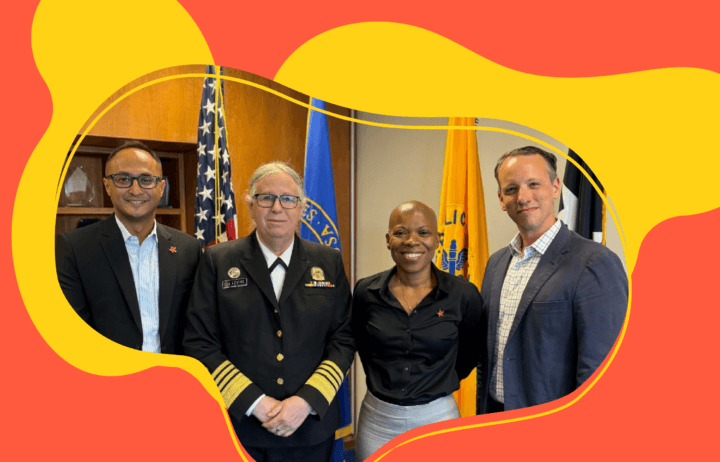

I am Preston Mitchum (he/him), an LGBTQ Attorney, Advocate, and Activist hailing from Dayton, Ohio and living and learning in the nation’s capital. I’m The Trevor Project’s Director of Advocacy and Government Affairs and the co-chair of our Black@Trevor Affinity Group.

I come to Trevor with a decade of advocacy and government affairs experience on a number of domestic and global civil rights and liberties issue areas, including abortion access, comprehensive sexuality education, HIV prevention, treatment, and care, sexual assault prevention, and police and policing. I’ve been privileged to work at nonprofit organizations such as the Center for American Progress, the Center for Health and Gender Equity (CHANGE), Advocates for Youth, and URGE: Unite for Reproductive & Gender Equity and write on a number of these topics. I’ve also been grateful to instruct on sexuality, gender identity, and the law at institutions like Georgetown University Law Center and American University Washington College of Law.

I come to Trevor as a person who has not only survived suicide loss but my own attempt at 20 years old. I come to Trevor fully understanding that mental health and suicide prevention policies writ large don’t take Black LGBTQ people into account, and many offer a vastly linear approach to identifying problems and creating solutions. I come to Trevor hoping to be a “possibility model” for other Black LGBTQ people who think they’re alone, like I did when I was younger. I come to Trevor fully ready to gently interrogate what it means for organizations like ours to center the most marginalized identities in tangible ways that impact law and policy.

One thing I am clear about is my refusal to separate my Blackness from my queerness. I don’t walk into any room just Black or queer, I proudly enter as both, always.

One thing I am clear about is my refusal to separate my Blackness from my queerness. I don’t walk into any room just Black or queer, I proudly enter as both, always. And that matters. I’m always reminded of Audre Lorde’s quote: “We don’t have single issue struggles because we don’t live single issue lives.” Over the past decade, it has become much easier to navigate spaces — big and small, corporate or nonprofit, Black or white — because the alternative of not being who I am is much more debilitating.

Many of us are finally starting to learn that Pride was not only a moment of joy and celebration— it was also a riot. Through the late 1960s, police consistently raided gay establishments simply to destroy LGBTQ-friendly spaces. In 1969, hundreds of LGBTQ people of color led the first major action against the NYPD in Greenwich Village at the Stonewall Inn. Though the historical record of Stonewall is often debated, Marsha P. Johnson, a Black transgender woman, is frequently credited with throwing the first brick at Stonewall. We also acknowledge the organizing and spirit of people like Sylvia Rivera.

Stonewall was one of many LGBTQ protests against police raids and law enforcement brutality. Cooper Donuts Riot was a small uprising in Los Angeles in response to police harassment in 1959. In 1966, at Compton Cafeteria, LGBTQ people, and transgender individuals in particular, fought back against police violence after vehement anti-trans harassment. And in 1967, two years before Stonewall, the LAPD entered the Black Cat Tavern as undercover police officers and started beating patrons as they were ringing in the New Year. All that to say, Pride was a riot that started because we wanted to experience joy, and that must be revisited during Black History Month too. Why?

Joy is resistance. Joy is revolutionary. Joy is necessary for sustained work.

Joy is resistance. Joy is revolutionary. Joy is necessary for sustained work. If I’m being honest, one of the most difficult things for me to do was celebrate. And, in many ways, it still is. That’s often because I know many people will never get the chance to celebrate until those with privilege and access to resources help to subvert systems rooted in dangerous and violent ideologies. Every day I learn the beauty of radical joy and rest and learn to trust those who are most negatively impacted by systems.

The hard truth is that society doesn’t know how to view Black people outside of trauma and pain. Trauma is profitable where joy is not.

I cultivate joy by centering health and wellness with other Black people. I cultivate joy with loud laughter. I cultivate joy with direct action organizing. I cultivate joy by writing honestly and accurately about Black LGBTQ people.

There is no America without Black people. There is no world without Black people. We are, respectfully, the fabric that ties together everything that is right, even without being given proper resources to make it so.

When I think of Blackness, I think of our rich legacy and connectedness. I know that without Black people — including our culture, presence, and contributions — institutions will look fundamentally different and not reflect who we are. Despite us not being monolithic, there is a connection once Black people just see each other. That’s what I love most about being Black and about Black people. Perhaps what I love most about being Black is understanding that we don’t have to be resilient as that often focuses on “resilience” but rarely the systems that force us to be so.

What I love about being queer is subverting systems that never existed before our discovery. What I love about being queer is our own self-discovery and unflinching understanding by many that we don’t have to follow cishetero standards to be loved, to find love, or to give love.

The beauty of both is that when combined, Black queerness is nothing short of magic. I’m reminded of that every Black History Month.

Preston Mitchum is the Director of Advocacy and Government Affairs at The Trevor Project, the world’s largest suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer & questioning (LGBTQ) young people. If you or someone you know is feeling hopeless or suicidal, our trained crisis counselors are available 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386 via chat www.TheTrevorProject.org/Get-Help, or by texting START to 678-678.